The Grand Budapest Hotel, for all of its frothy pink decor and exteriors, is at its core just an exquisite film about loneliness. Everyone in the movie is lonely for most of it. Zero, who has lost his whole family, country, and even his name, is perhaps the loneliest of all, but he is hardly the only ones. The old women that stay at the hotel are surrounded by fluttering entourages but know in their heart of hearts that people only care about them for their money. Agatha, the real talent behind Mendl’s, has no family, no history of her own, and spends most of her life under the stifling thumb of her employer. Even M. Gustave, around whom the whole hotel revolves and who provides comfort to so many lonely old women, is lonely himself and returns to his tiny room to write letters in his ridiculous sock garters. He is unable to separate himself from the hotel, and perhaps does not want to—he is reluctant to speak about his past, hinting at some off-screen tragedy. For all intents and purposes, M. Gustave is the hotel and nothing else. M. Gustave is a man that cannot exist with his facade as the hyper-capable concierge. The moment he starts to open up to Zero about his personal life and past, he is killed.

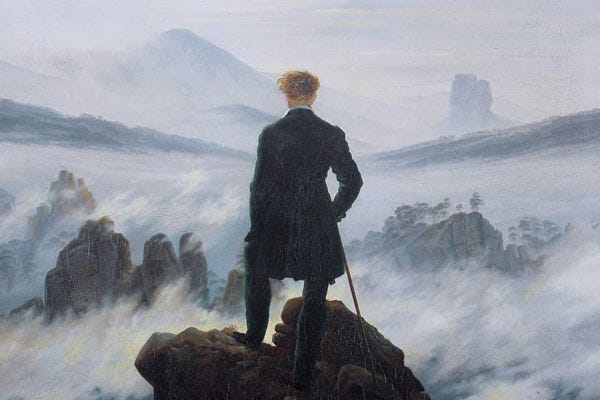

Even the landscapes are lonely. In an interview, Wes Anderson said that certain scenes were inspired by the landscapes of Caspar David Friedrich, a German Romantic landscape painter whose paintings often position lonely figures before dramatic natural scenes. Compared to the vastness of the world, we are very small indeed, which makes the few moments of connection the people in the film (and we ourselves) manage to grasp that much more precious.

However, the most poignant loneliness in the film is not the loneliness that comes from not having family or friends. There is the loneliness of living in a world that is becoming increasingly brutal and knowing that nobody else cares. For all the fun hijinks of the caper in the story and beautiful scenery, this is a movie set against the very real backdrop of fascism, one in which any of the main characters—Zero (a refugee), Gustave (implied bisexual), M. Kovacs (Jewish), and maybe even Agatha, (her backstory is unknown, but she is shown to have a Toil & Servitude permit and Mendl is a Jewish surname)—will suffer, and they certainly don’t have anyone else to count on to help them. Just take the tragedy of M. Gustave’s last scene. Ralph Fiennes does an amazing job of showing the character’s crushing realization that this time, there will be no genteel Nazi coming to save him. The man who made so many people feel less alone did not receive the same favor.

M. Moustafa in the present day is also deeply lonely, not just because he lost everyone that he’s ever held dear, but because the world refuses to acknowledge his grief. The world moved on, occupied with the living that it has to do. Perhaps it is better to move on, because to stop and examine what was lost is to realize that in a way, fascism won—it killed millions of people and destroyed an entire world order, one that will never come back. That is why M. Moustafa seeks out the writer that is our narrator. The writer himself says that people often bring stories to writers once they find out that a person has that profession. This act of profering up stories, is an act of loneliness. It is a person saying, “there is nobody in my life to hear me, so I am bringing my story to a stranger. Please take it.”

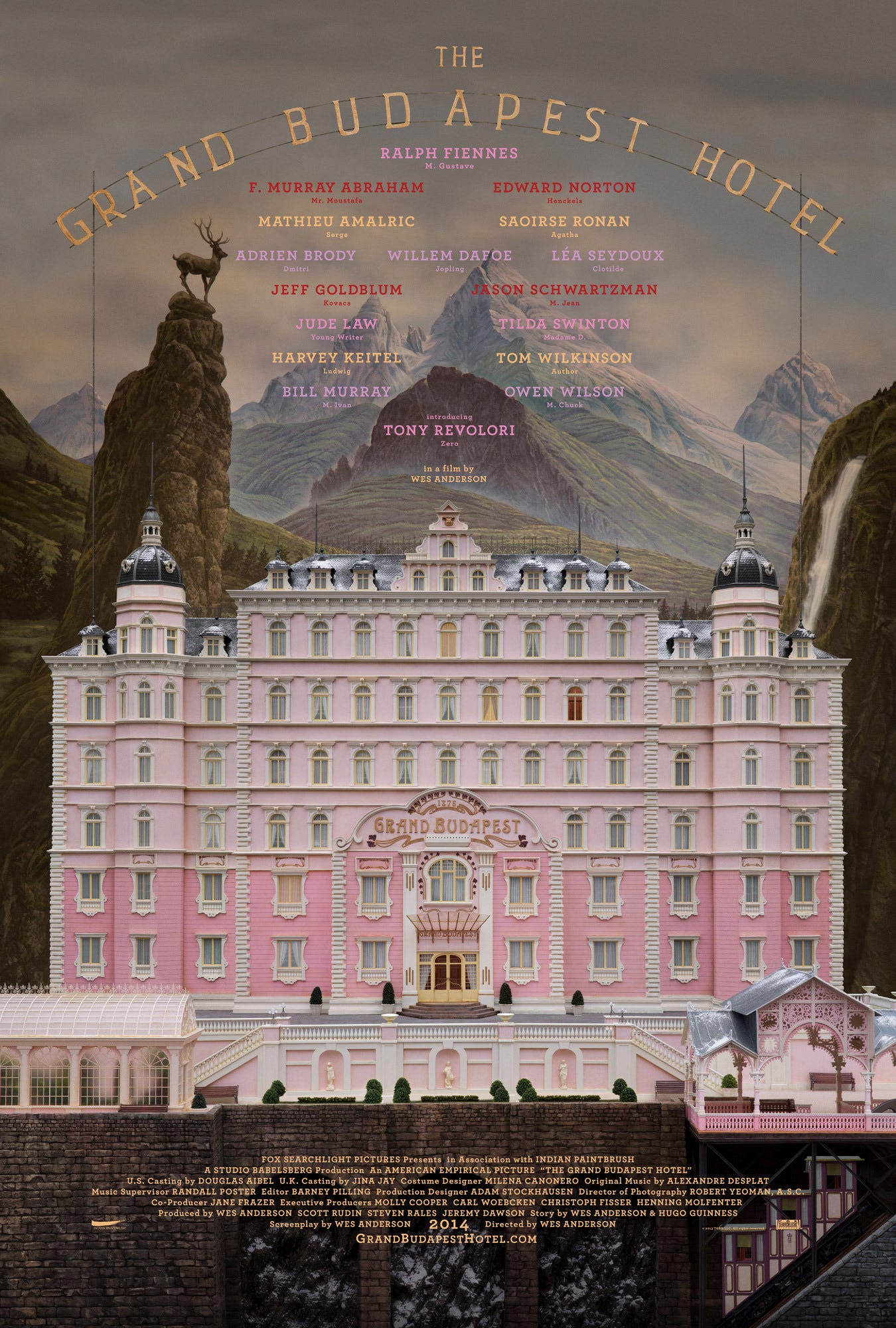

The hotel itself is a victim of loneliness. In its heyday, it is a place of liveliness and gathering. People dance in the ballroom, mingle in the restaurant, come here to see and be seen just like they did in the old spa towns of the Hapsburg Empire that it is clearly based on. But in the 1960s flashbacks chronicling the hotel’s decline, everyone is alone. Nobody talks at dinner, and even in the thermal baths, people soak in their own bathtubs instead of the communal pool (thermal baths are a shared experience to this day in places where they are active. A friend of mine made friend with an old Hungarian man by playing chess at the Gellert Baths). As soon as people prefer their solitude to the company of others, an institution like The Grand Budapest cannot survive.

The other, obvious theme of the movie is nostalgia, which is just another way of expressing loneliness. Only lonely people are focused on the past, the happy have enough to occupy themselves in the present.

The film was heavily inspired by Stefan Zweig’s The World of Yesterday, a memoir about the author’s time growing up during the dying days of the Hapsburg empire with emphasis on the culture and intellectual exchange of the time. He talks about the freedom and values he enjoyed during the time, values he lost as an Austrian Jew in the 1930s. The day after he posted the manuscript to his publisher, Zweig died by suicide in exile in Brazil.

I am a massive of fan of Zweig’s memoir, although my copy of the book got left behind at my mother’s place during my move. However, I can’t stop thinking of a critique I saw on Twitter (although I’ve sadly forgotten the author), which pointed out that the world Zweig describes, one of genteel intellectual pursuits and free movement across Europe, was an idyll that only the wealthiest could ever hope to experience. This is true even of the idyll of The Grand Budapest Hotel, where the servants that make it tick are confined to closet-sized rooms and work inhumane hours, far from the luxury downstairs.

Unlike Zweig, the film knows that the nostalgia it is building is for an imaginary place and time. After all, it is set in an imaginary hotel in an imaginary city in an imaginary country overrun by an imaginary Nazi army. The hotel is actually an abandoned department store in the east German town of Gorlitz, near the Polish border. The geography of the film is merrily eclectic: there are references to the Czech Sudetenland, the hotel is modeled after the great Czech spas of Karlovy Vary and Marienbad, and the name of course is a reference to Budapest in Hungary. Anderson himself cites several Central European countries and cities, including Prague, as inspiration. The soundtrack by Desplat pulls influences from even further afield, including Swiss traditional yodeling, Russian folk music, and motifs that reminded me of Croatian and Serbian tamburice playing even if there are no explicit acknowledges of those references. The film knows that it is nostalgic for a unified, genteel Europe that never existed, so it just invented it.

The final proof that the film knows its hazy nostalgia is all illusion comes from M. Moustafa himself. Speaking of M. Gustave, he says, “To be frank, I think his world had vanished long before he ever entered it. But I will say, he certainly sustained the illusion with a marvelous grace.”

The film opens in the 1930s, long past the heyday of the great Central European resorts, during the last gasps of the Hapsburg Empire. Anderson perhaps brought the timeline forward to compress the pre-war sentiment before World War I and II and to add the creep of fascism to the story, but it works well. Even if the other Grand Budapests of this world were collapsing under the creep of national borders long before the creep of fascism, M. Gustave managed to preserve his hotel. That is a testament to his skill. The illusion is cultivated even in the present day, the nostalgia lives on.

During the first time Zero’s papers are examined, Gustave says, “You see, there are still faint glimmers of civilization left in this barbaric slaughterhouse that was once known as humanity,” implying that there once was a civilization. In truth it was never there, not for those without his riches and connections. There will be no civilization waiting to save us, and the ones we rely on are quick to fall. The best we can do is save each other from the barbaric slaughterhouse of humanity, and the crushing weight of loneliness.

After all, as the cheery tale of The Grand Budapest Hotel taught us, there will be nobody else coming.

brilliant

Really great essay! Thanks!