It is time for a new Wes Anderson, and this time I was able to catch it during the nanosecond that it was playing in cinemas in my small Serbian city, like most indie films.

I miss living in a place that has indie movie theaters. I miss a lot of things that are not in Niš, including not having to plan my movie outings around the rare moments every 3 months when one of our 3 multiplexes in town plays something that isn’t a kid’s cartoon or Marvel slop. There are, however, benefits, and one of those is that I was the only person in my screening at the multiplex in the mall and didn’t have to worry about looking underdressed and uncool for Wes Anderson.

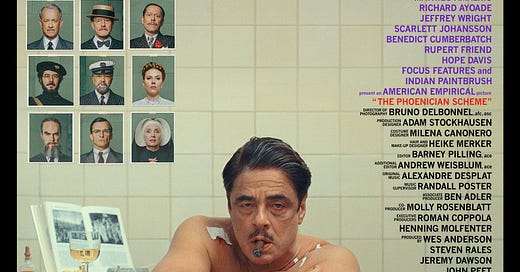

The Wes Anderson movies I’ve seen are about lonely rich people, lonely children, or both. The Phoenician Scheme follows Zsa-Zsa Korda, a supposedly brilliant and ruthless businessman, on a humbling quest as he tries to fund a massively ambitious project. For all the talk about Zsa-Zsa’s business acumen, he doesn’t display much throughout the film, resorting to infantile tactics and slapstick violence that still barely yield what he wants, and being fooled by a transparently bumbling [nameless character] (at one point, the secret agency handlers joke about his brain damage sustained after multiple airplane crashes as an explanation for his mistakes).

Along for the ride is Liesl, his estranged daughter, a novice nun he has had barely any contact with and who suspects him of murdering her mother. Zsa-Zsa summons Liesl from her nunnery to make her sole heir and executor to his estate, despite his nine sons that live with him in a state of (not so) benign neglect. Mia Threapleton is fantastic as Liesl (we will make an exception for nepo babies this time), giving the character a toughness without betraying her youth or her genuinely held religious principles. It is interesting to see a character who has such a strong, sincere relationship to her faith (although it is challenged by her own rediscovered love of the nice life and by revelations of the Church’s grubby nature). She is also the sources of one of the greatest visual gags in the movie, the slow addition of modish details to her plain white habit, so that by the time Mother Superior tells her that she isn’t cut out to be a nun, under the greed for patronage from a newly wealthy former novice is a scene of genuine recognition from one that also admires nice things, as the perfectly-timed close up to Mother Superior’s cross shows.

As always, every frame is meticulously planned and visually stunning. However, here each scene is carefully crafted for an even higher purpose, for providing the greatest payoff for visual gags. At times, the effect is like what if one of our greatest living directors directed a Tom and Jerry short, but in a positive way. The entire film relies on the juxtaposition of beautiful setting and cartoonish violence to great effect (Wes Anderson challenging the “nothing ever happens in a Wes Anderson movie” crowd).

I mentioned earlier that below the beautiful visuals in a Wes Anderson film is almost always a well of loneliness. Here, Zsa-Zsa’s wealth covers a profound loneliness that started when he grew up in a frigid, competitive wealthy family, which despite his jokes about it made him unable to form meaningful connection his entire life. During an argument, I recently told my partner that there are two types of people in this world, those who’ve felt the conviction that nobody will ever love them and those who have not, and Zsa-Zsa belongs to the former category. It is why, as the movie goes on, it becomes harder for him to bear the truth of Liesl’s parentage. His growing awareness of his own loneliness is something that Benicio del Toro plays magnificently.

For Zsa-Zsa, amassing wealth is a coping mechanism–but it is also the thing that is alienating him the most from his fellow man. During his first dream of God’s Heavenly Judgement, his own grandmother turns to him with disbelief and asks him who he is. In turning himself into a myth, he has rendered himself unknowable even to his own family.

As Zsa-Zsa’s repeated encounters with heavenly judgement show, “it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God” (Matthew 19:24). The judgement sequences are some of the most stunning that Anderson has ever put on film (am I the only one that detected some influences from Parajanov?) and they are left deliberately ambiguous—are they dreams, sincere visions, or hallucinations? These themes are even more interesting considering that the film is dedicated to his father-in-law, Fouad Malouf, a Lebanese construction entrepreneur.

The Phoenician Scheme is billed as a caper, but it is really a fairy tale. The rich man loses his money but learns to be good and hard-working. The lonely children get a father and an older sister/mother figure. It is one of the most unambiguously happy endings out of the Wes Anderson movies I’ve seen so far. In true Shakespearian genre conventions, it even ends with hints of a wedding.

I leave the movie, joking with the kid attendant about how I was the only person in the screening. I hate movie theaters in malls because the sensory overload of leaving the peaceful screening room and immediately entering the blaring mall is often too much for me. This particular mall is the fanciest one in Nis, one where the local rich people come to promenade and have coffee as well as shop. It feels small-town elitist, so much so that my partner felt uncomfortable going for a long time, but in a way that just makes me roll my eyes.

In the parking lot, one of the rituals marking the beginning of Nis summer has begun. A sports car with foreign plates belonging to a Serbian living abroad is driving slowly through the parking lot so that the local kids can look at it. Today, it is a Lamborghini driving slowly as packs of Nis’s richest 7 year olds follow on their bikes clutching smartphones and filming. The local performers of wealth are exposed by their own children, who gawk at luxury automobiles the way the (gasp!) poors normally do, showing that their parents are not quite a cut above the rest at all. The gastarbajteri happily show off in their country of origin, but this behavior would be considered declasse in their new homes.

Everybody is performing, but nobody knows who is the audience, or why they’re bothering in the first place.